Roads that Separate

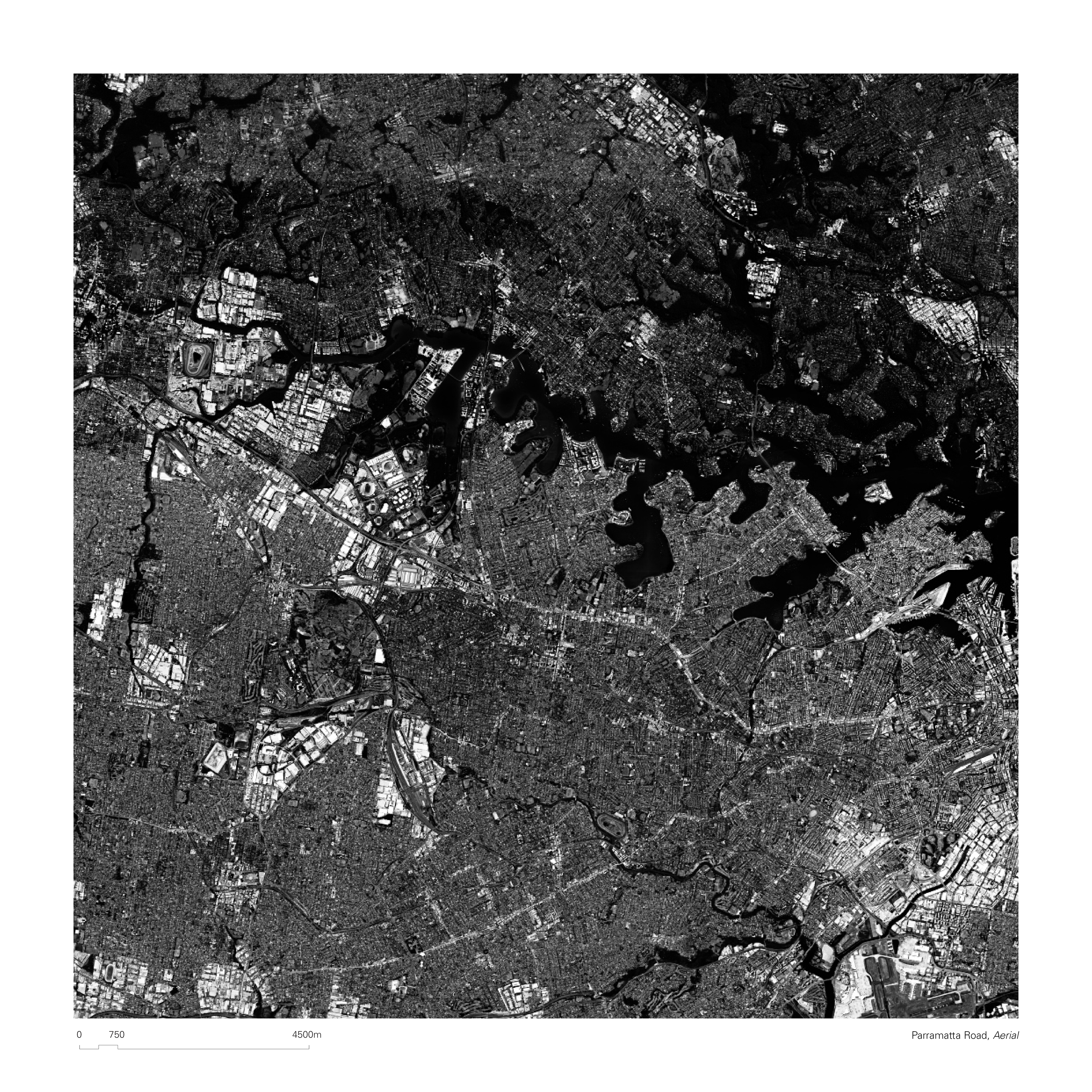

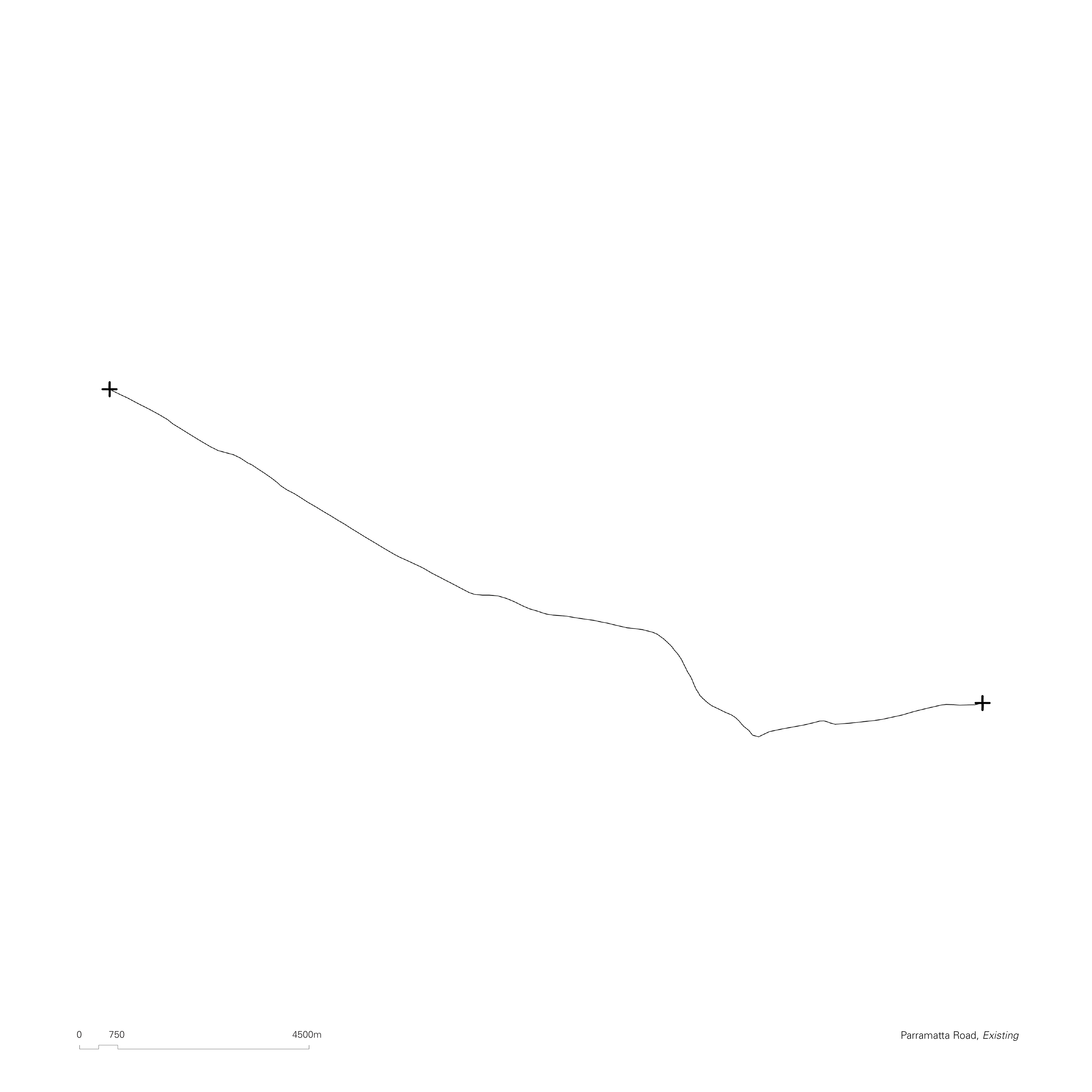

Parramatta Road is a twenty-three-kilometer major artery which runs east to west across most of metropolitan Sydney. Built upon an Aboriginal walking track used by the Gadigal, Wangal, and Wallumettagal peoples of the Eora Nation and the Burramattagal people of the Darug Nation, Parramatta Road has operated for thousands of years as a successful trade route. Through its evolutions, it exists as the embodiment of the intrinsic relationship between economies and urban patterns. The intent of the following proposal is to question the role of Parramatta Road in the context of Sydney – today – as a boundary rather than a connecting device.

Speed increases in our systems - whether they be vehicular, financial, or informational - have extended the reach of our ever expanding urban and social structures. Velocity supersedes distance. Everything and everyone always available, through a particularly sleek and uniform experience – whether it be the highway, the shopping mall, or the smartphone. Arteries like Parramatta Road enable the continuous sprawl of cities into infinite planes, endless flows without a beginning nor an end, in an implicit act of division. They do so in accordance with what Pier Vittorio Aureli defines as the “smoothness of global economic trade,” (Aureli, 2011) the primary and essential raison d’être of modern urbanization.

Throughout the twentieth century countless voices - from Mumford to Lynch and Jacobs - warned us about the dangers of the glossy modernist dream. Today, it has become increasingly clear that the standardised commodification driven by urbanization is stripping our cities of localized trade and eradicating their distinctive urban fabrics.

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Endless Flow

Walls that Connect

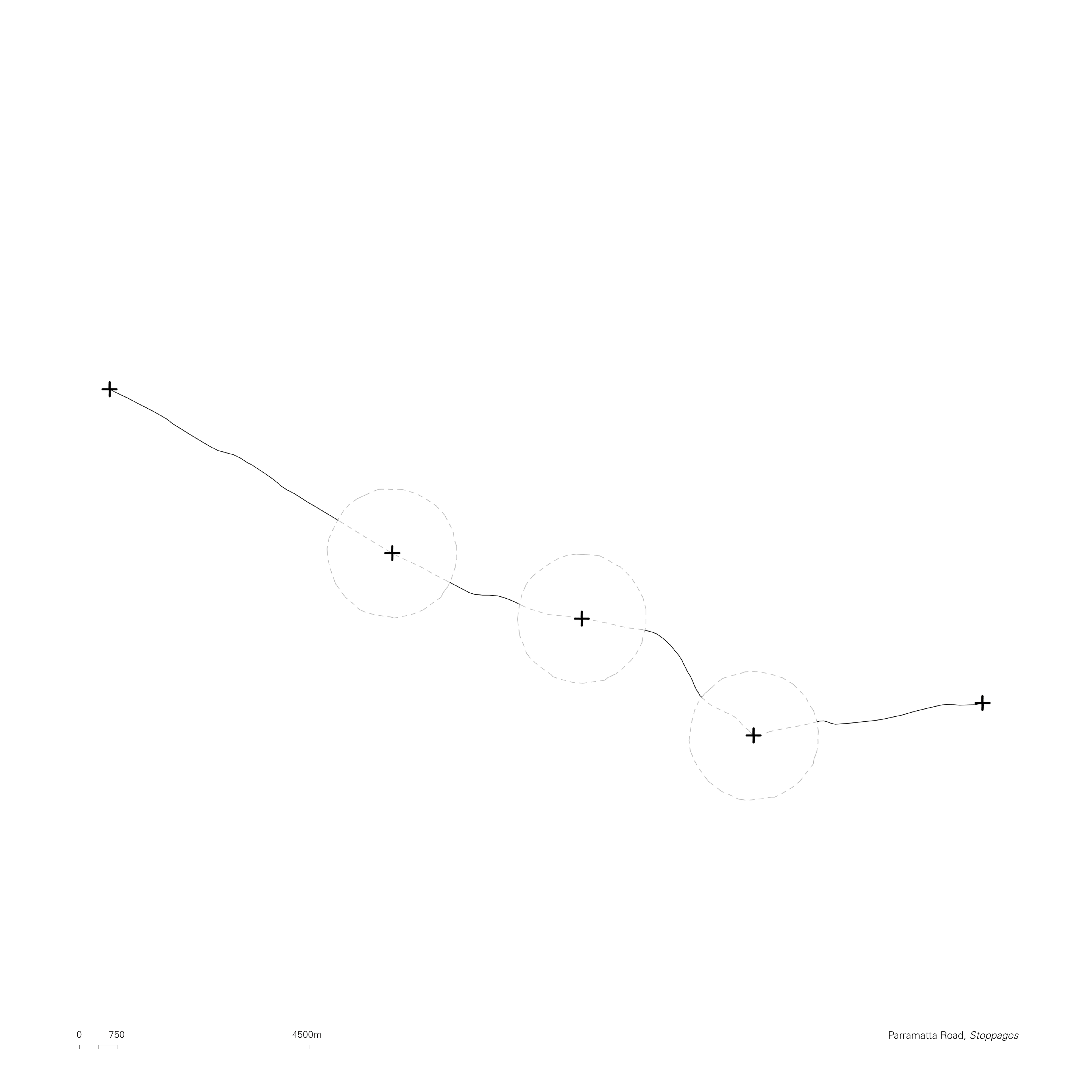

By acknowledging the central role trading systems play in the shaping of our cities, the following project proposes the insertion of physical obstructions – envisioned as souqs which embody a renewed typology of trade – along Parramatta Road, as interruptions to its currently infinite and homogenizing flow. These discrete elements don’t act as separating devices, but rather as points of reference within the current urban sprawl. Initially acting as enclaves of regeneration and radical locality placed along the artery, they will begin to interact with each other creating a new network of civic connections and by doing so, will also redefine the fragmented road between them. The gradual dissipation of Parramatta Road as a mega-structure is envisioned as an opportunity to redefine its scale and character, returning it to a human one.

“In giving this sociological answer to the question: What is a City? one has likewise provided the clue to a number of important other questions. Above all, one has the criterion for a clear decision as to what is the desirable size of a city – or may a city perhaps continue to grow until a single continuous urban area might cover half the American continent, with the rest of the world tributary to this mass? From the standpoint of the purely physical organization of urban utilities - which is almost the only matter upon which metropolitan planners in the past have concentrated - this latter process might indeed go on indefinitely. But if the city is a theater of social activity, and if its needs are defined by the opportunities it offers to differentiated social groups, acting through a specific nucleus of civic institutes and associations, definite limitations on size follow from this fact.” (Mumford, 1937)

Returning Parramatta Road to the City

In the collective mind, Parramatta Road is seen as an unsuccessful civic asset. The current New South Wales road minister, John Graham, often refers to it as “the scar through the heart of Sydney.” Indeed, the intensity of the traffic between Sydney and Parramatta has hindered the growth of any alternative centers between them. While connecting the two primary CBDs, the road acts as a boundary for everything else. The street scape of Parramatta Road, mainly composed of run-down Victorian storefronts, industrial warehouses and car dealerships, proves as evidence that the daily average of 100,000 cars using the road do not stop on it, contributing to its economic drought. At a pedestrian scale, the vehicle speed makes the road feel unwelcoming and unsafe, further contributing to its failing retail operations. It is estimated that in 2020, two-thirds of its local storefronts were vacant (Committee for Sydney, 2020). An attempt to disrupt Parramatta Road and recompose it is therefore a political and financial confrontation, as well as an urban one.

The boundary that is Parramatta Road today has the potential of becoming one of Greater Sydney’s greatest civic assets and relieve thousands of citizens from the current urbanism which reigns as an “economic logic of social management” (Aureli, 2011). A place – or places – to be, rather than to transit through. An opportunity to uncover and celebrate the rich history of Parramatta Road currently buried under a thick layer of asphalt and concrete, creating communities centered around shorter supply chains, domestic trade and a deep connection to Country.

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Industrial Site

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Petrol Station

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Commercial Site

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Shop Front Terrace

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Shop Front Terrace

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Shop Front Terrace

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Car Dealership

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Car Dealership

Existing Fabric of Parramatta Road, Car Dealership

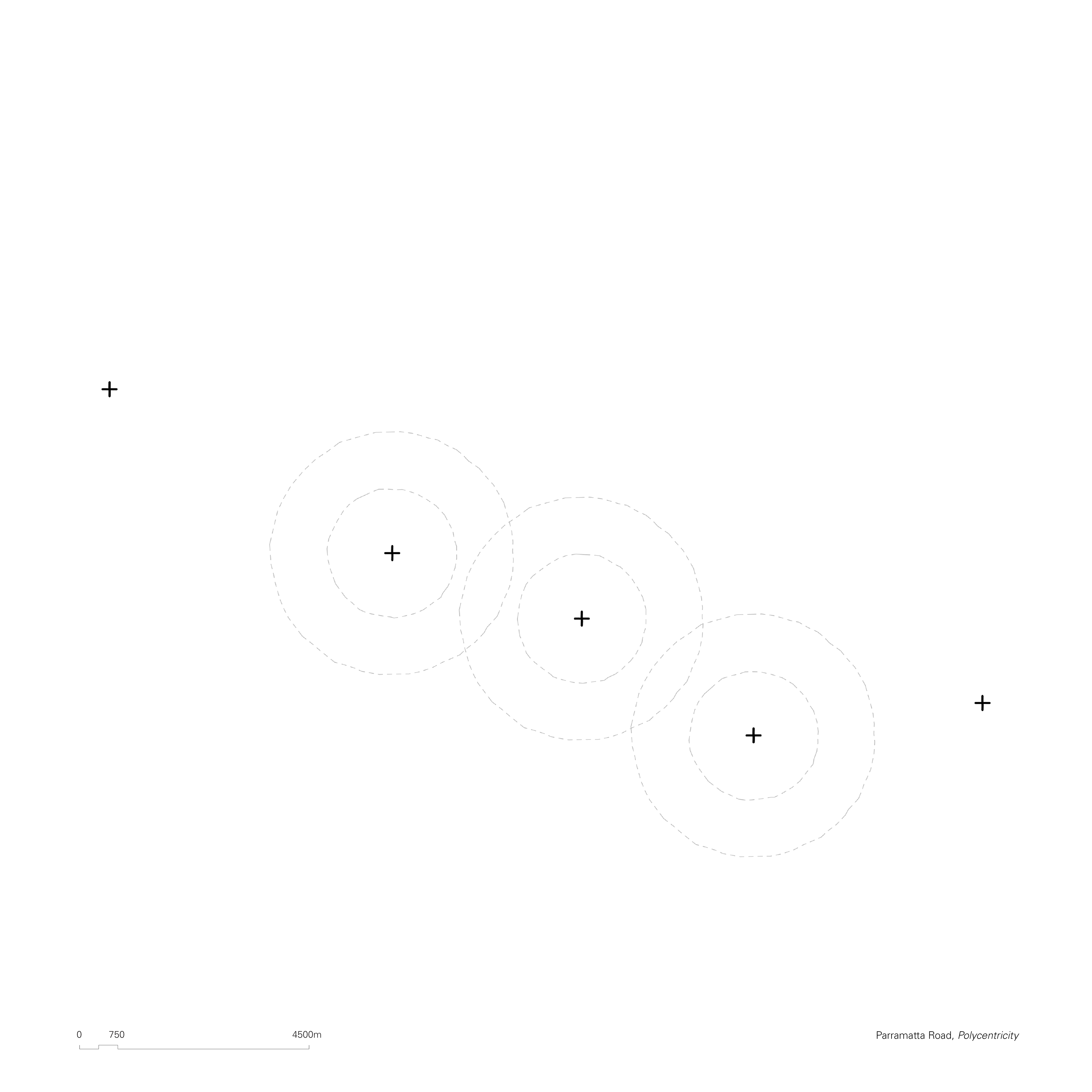

Polycentric Stoppages

We propose that economic and financial activity, absurdly and disproportionately condensed in today’s CBDs, can be distributed more evenly at smaller centers. These smaller centers will facilitate economic and financial activity at a more localized scale, with a smaller radius of influence. This localized scale provides opportunity for an urbanism that is less reliant on vehicle transport, as well as contributing to the development of a clear character of place.

The endless flow through Parramatta Road will become less dominant, and more locally fragmented. As these centers develop, their circles of influence will begin to overlap, developing more intricate networks of connection, between finer nodes, eventually eradicating the need for such dominant arterial connections such as Parramatta Road. The stoppages, envisioned as “fish traps,” are to be porous entities, able to envelop the desired trade, while allowing other systems – peoples, living beings, water, landscape and so on – to freely pass through its boundaries.

Porous Fishtraps

Existing a seminal mode of trade for First Nations clans for thousands of years, Parramatta Road is perhaps the oldest, active trading route in the world. While the surrounding landscape has been severely altered, historical records show us that the location of the path, following the low ridges of the area, has remained largely unchanged. The original path has been gradually – and sometimes abruptly - adapted into its current form. Analyzing the geological conditions of the site helps us understand what the harbour would have looked like prior to industrialization.

What emerges is that the walk track, traversing territories mostly defined by Ashfield Shale, would rhythmically intersect with fertile land made of silt, clay, and fine sands, which indicate the vicinity of a water stream stemming from the harbour. These locations would have been important places of trade – natural stoppages within the path - as well as culturally and spiritually relevant ones.

Such intersection points offer a unique opportunity not only to re-establish our built form in relation to the cultural heritage of the land, but also as a means to introduce landscape corridors which can reconnect Parramatta Road to the harbour shoreline. Three locations along the road have been identified for our proposal: Summer Hill, at the intersection with the Hawthorne Canal; Lidcombe, towards Haslams Creek; and Burwood North, at the junction with Burwood Road. The latter has been further developed as a case study for future applications.

The Organisation of the City

Social Facts

Our polycentric propositions and what we define as their area of influence rely on the same concepts discussed by Carlos Moreno in his seminal work “The 15 minute City.” Moreno’s research is rooted in a deep and nuanced understanding of civic life and its interrelationship with urban patterns. While infrastructure such as highways and railroads (and the internet) exponentially accelerate our mobility and connections, technically providing us with “15 minute cities” with endless radiuses, the activities of small children, as noted by Mumford but clearly also articulated by Moreno, “are still bounded by a walking distance of about a quarter of a mile.”

In order to provide integrated civic spaces, we must consider the needs of diverse groups of people and maintain a cross-generational approach. Through such lens, the pedestrianizations of our suburbs is an environmental consideration just as much as a social one: the proposed stoppages along Parramatta Road will each have a one-kilometer diameter which defines its “zone of influence,” being the areas of the existing urban fabric served by the intervention, as well as delineating the extent to which that stoppage can expand into.

In order to provide integrated civic spaces, we must consider the needs of diverse groups of people and maintain a cross-generational approach. Through such lens, the pedestrianizations of our suburbs is an environmental consideration just as much as a social one: the proposed stoppages along Parramatta Road will each have a one-kilometer diameter which defines its “zone of influence,” being the areas of the existing urban fabric served by the intervention, as well as delineating the extent to which that stoppage can expand into.

The imposed walkability of city whose existence pre-dated that of a car allows it to retain a particular social atmosphere, as often pointed out by Manuel de Solà-Morales in his publications. As if the compression of urban functions within a given perimeter – dictated by protective walls, topography and so on – allowed for the emergence of a fragmented unity, an archipelago of civic functions co-embedded through a strong texture of place.

An aura experienced by the physicality of walking the street: the way in which your senses engage with it at the pace of the human foot, un-replicable if sped up through machines. Paradoxically, the positioning of the old city as a stoppage within the smooth flux of modern “economic social management” is what gives it civic value.

The Chosen Site

The proposed site is located at the junction between Parramatta Road and a secondary arterial road, Burwood Road, which leads to Burwood town center to the south, and the suburbia of Concord to the north. The junction at Parramatta road is currently an abrupt threshold for vehicles travelling in and out of the town center or suburbs. Burwood town center is dominated by Westfield, a commercial shopping enterprise, but also bound by fine grain, multicultural businesses which thrive on the main street. Concord holds multiple public amenities, as well as underused green space which has the potential to create a connection corridor between the chosen site and the harbour.

The current condition of Parramatta Road at the site is typical – large industrial facilities and mostly empty shopfront terraces run across the road, with low-density housing right next to it. Despite this, the existing key civic assets located in close proximity to the midpoint of Parramatta Road define the potential for a successful insertion of an urban node. The potential of the area has already been acknowledged by state planners, with a new Burwood North metro stop scheduled for opening in 2032 right next to the chosen intersection.

Borrowed Thoughts

“One further conclusion follows from this concept of the city: social facts are primary, and the physical organization of a city, its industries and its markets, its lines of communication and traffic, must be subservient to its social needs. Whereas in the development of the city during the last century we expanded the physical plant recklessly and treated the essential social nucleus, the organs of government and education and social service, as mere afterthought, today we must treat the social nucleus as the essential element in every valid city plan: the spotting and inter-relationship of schools, libraries, theaters, community centers is the first task in defining the urban neighborhood and laying down the outlines of an integrated city.”

(Mumford, 1937).

(Mumford, 1937).

Planting the Seed

01.

The initial intervention proposes a walled zone which encapsulates the chosen site, in an attempt to convert it from a traffic diverging point to a central node, by acting as a physical obstruction that interrupts, restricts and alters traffic flow. The Wall acts as a piece of protective infrastructure for the incubation of a localized economic center. At the center of the proposal will be a large public courtyard, a landscape area which takes cues from civic squares and translates them through a distinctively Australian lens. The interplay between the focal object (the Square) and the frame (the Wall) creates a porous in-between, an intricate network of pathways that create unique building footprints, to be occupied as a souq and its supporting infrastructure. The geometrical purity of the Square elevates its symbolic and social status within the development, in constant dialogue with the enclosing Wall, which instead moulds its geometry to the existing fabric.

The zone of influence of the node is defined on the arterial roads by a set of “portals,” which sit one kilometer in diameter from the center of the public square. A walking distance away. The portals initiate the slowing of traffic by reducing vehicle lanes from six to two and increasing pedestrian footpaths. This provides an opportunity for the area between the portal and wall to be reinvigorated by foot traffic as well.

02.

As the Souq develops and the seed grows, the boundary delineated by the wall may begin to be superseded. Growth is defined by the logic of the network established by the pathways within the Wall, which project out of its openings. The wall, to an extent, begins to dematerialize. Punctured by new openings, some of its materials may be used for further construction. Entire parts of the wall may be removed. One might decide to build on top of the wall directly. The wall is not to be considered precious. Rather, it is to be utilized as a piece of evolving social infrastructure.

This logic set by the pathways redefines the rectilinear suburban grids developed for efficient urban sprawl stemming from Parramatta Road. At the core of this growth is responsible density. Streets are kept tight, promoting a tight knit urban fabric, as opposed to a loose sprawl. The intricacies in the urban tapestry developed through this slow growth establishes a network of fine grain connecting pathways which embody a slower, more localized urban economy.

03.

As the seeds grows towards the boundary set by the portals, the precinct is now envisioned as a vibrant amalgamation of trade activity and urban life. The new buildings, bordering the zone of influence, in effect create a protective layer for the activity within, while also establishing better amenity for the surrounding streets. They thus become an invisible wall, in conversation with the established portals, which replaces the need for the strong, physical boundary initially set by the original Wall.

Phase 01

Phase 02

Phase 03

Geometry, Scale

A carefully considered interplay between three primary grids allows the emergence of the complex network of streets which define the project. Envisioning a gradual development, it was important that the proposal would remain amicable to the existing street pattern. The primary grid is set by Parramatta Road, 79.87 degrees to north. As Burwood Road was initially built perpendicularly to Parramatta Road, most of the existing fabric to the south of the proposal follows this set out. The secondary grid is dictated by Gipps’ Street angle, 66.30 degrees to the north, which defines most of existing buildings between the chosen site and the harbour. Additionally, a third grid – aligned to true north – is integrated. Geographic coordinates are specifically important to First Nations cultures as means to create a tangible connection between the built environment and the land, water and skies. In the context of the proposal, it allows us to achieve a strategically crafted relationship between meandering pathways and primary thoroughfares throughout the proposal.

The scale of the proposal has also been methodically conceived. A thorough analysis of the current built form around the site highlighted the intense juxtaposition between the industrial activity on Parramatta road, the low-density dwellings adjacent to it, and the imposing tower developments running across Burwood Road. The current strategy is amplifying the disconnect across the intersection and actively deteriorating the quality and atmosphere of the precinct. The proposed intervention on the other hand, with a four-storey height limit, balances the need to provide additional housing and amenities while maintaining a respectful relationship with the built form of the existing dwellings.

Living & Working

A variety of architectural typologies are proposed to reflect the envisioned nodes, operating at different scales, functions and lifespans. Designing a diversity of typologies is a response to the diversity of lifestyles emerging in the 21st century which challenge, as Aureli outlines, traditional notions of labour, reproduction and the concept of the domesticity as a whole.

Aureli and Tattara concur on the fundamental complicity of our built environments in the perpetration of societal binarisms: male/female, breadwinner/housewife, private/public, productive/unproductive. Indeed, the commodification of the household as a spiritual retreat has divided the tasks necessary to live along the binary of commercial capital, inexorably relegating part of the population to the home and the home only. In order to revitalize small scale businesses, we believe primary services should be radically integrated in the fabric of our cities, by breaking down outdated dichotomies between productiveness and unproductiveness, in order to facilitate a more holistic engagement with our work environments and civic spaces.

Diverse modes of trade, economies and work empower the diversification of lifestyles, but require an architectural framework to do so. The architectural proposal thus questions the boundaries of living & working by facilitating a ground for negotiation, arguing that the interrelation of these realms will enables more localised modes of urbanism to emerge.

People, Movement

Programmatic co-embeddedness begins with the primary constituents of the city: its inhabitants, and their movement. When thinking about our urban seed and its ability to flourish, it became apparent that in order to provide a rich tapestry of place we had to consider a diverse range of users and the programs required to sustain them.

Different People

Catering for a variety of demographic age groups allows the propositions to remain socially activated at various times of the day and through a diverse range of modalities. This includes providing targeted housing as an opportunity for people to downsize at later life stages of life without the need to abruptly relocate, as well as supplying affordable housing for younger people to establish blossoming and regenerating communities. It is also crucial that the necessary programs are provided for merchants to live in place, to contribute to the liveliness of the intervention from a social standpoint, on top of a financial one. Beyond store holders and inhabitants, the intervention must account for people visiting. Being able to provide programs such as libraries or shared office spaces will incentivize people to travel to the site and engage with the local trade, such as picking up groceries on the way home.

Different Movement

Merchants trading outwards, visitors travelling inwards, and inhabitants wandering within. The interplay between different movement patterns will further enhance the vibrancy of our civic intervention.

1:750 Model

1:750 Model

1:750 Model

Three Types of Souq

The proposed nodes operate as a continuous reciprocation between three distinct trade patterns, embodied by three typologies of Souq:

The Central Square hosts store holders which require an active spillage onto the public realm: restaurants, bars, produce vendors and so on will be able to use the ample public space as a stage for their trade, enlivening the public experience. The absence of residences within the square allows for louder activity to occur without creating disturbances.

A network of pedestrian pathways inhabits the space between the wall and the square, accommodating activities with a more subtle street engagement. The streets are defined by the human scale, providing an intimate street experience, as well as a residential one.

Finally, the node integrates the infrastructure necessary to host temporary markets in the main square, providing an opportunity for merchants who do not reside in the node to participate in its vibrant trade. Permitted vehicles will be able to park in the service area on Parramatta Road, signposting the presence of the markets to people walking by, and accessing the main square through a dedicated corridor.

01. Plaza Building

The central plaza is a public space at the core of the project, facilitating various functions integral to the souq. A native garden lies at the core of the public space, its most dense point at the centre, loosening out into a lawn. The perimeter of the temporary market space is outlined by the colonnade of the plaza building. On the ground floor, large, angled blades of rammed earth create a series of outdoor spaces that are sheltered by a fabric awning and deck above. The zone delineated by the blades creates a mediation zone between the open public space of the square and the souqs within the wall.

The space between the blades can be inhabited by the stores operating in the spaces in the wall. On the ground floor and first floor of the wall, spaces are carved into the rammed earth. In plan, the layout responds to the three grids previously mentioned, embedding the building to the site and creating a unique spatial experience in each room. The ground floor is suited for market spaces benefiting from interaction with public foot traffic, such as food and beverage, fresh produce and retail, whereas the first floor, elevated from the public square, is more suited for intimate dining and smaller scale trade. The irregular shapes produce a variety of interior conditions over multiple storeys, which are open to interpretation by merchants and store holders. Amenities which service the public plaza are also contained within this structure.

The second and third floor of the plaza building are semi outdoor mezzanine floors and is anticipated to provide sheltered public space. The roof structure, through its angled roof sheets, provides views out onto the public square, creating a visual connection between the two public zones. The second floor has glazed rooms which open up onto the mezzanine, providing amenity for functions and community events. On the third floor, views out to beyond the outer wall maintain the connection between the node its broader environment.

02. Temporary Markets

The temporary market space is defined by two rows of 5 metre squared grids, marked by reclaimed bricks on the floor between the cobblestone of the Plaza. Demountable canopy structures are provided by the municipality for those participating in the market, establishing a sense of collective ownership for stall holders. This sense of community is enhanced by the stall structures echoing the materiality and detailing of the plaza building. The temporary market infrastructure facilitates smaller scale, more casual forms of trade to occur as part of a larger economy of souqs.

Vehicles will be able to park along the designated shared-area along Parramatta Road. Service functions required to operate the temporary market are theatrically displayed to the public both as a way to signal the presence of the market as well as a way to celebrate the added value this type of trade brings to the node. Smooth paving facilitates the transport of the goods to the plaza, with the demountable canopies stored in a building along the way. The layout of the market is pre-determined by the ground pattern, creating rows of 3 metre canopies with 2 metre walkways in-between. The corners of the Plaza building are equipped with the amenities and auxiliary services necessary for the functioning of the market.

03. Street Souq

The street souq makes up the majority of the fabric of the node. It is the embodiment of the concepts articulated by Aureli and Tattara, suggesting a highly integrated relationship between domestic and public spheres. Building are placed along 7 metre paths, with 12 metre main streets connecting the node to the existing primary roads. Corners are at times chamfered, opening up the buildings to the street. The utilization of different paving helps to define the gradual boundaries between spaces.

The ground facades of the proposal are composed as thick, rammed earth walls. The depth of the walls enable them to be lightly inhabited in a way that is expressive and almost performative towards the street and the neighbourhood. Souq spaces on the ground floor inhabit the walls in the same manner as domestic spaces on the level above, where the merchants of the souq beneath reside. The chosen slab construction method helps to prevent unwanted noise from entering the homes, as well as providing a strong structure for diverse types of retail ceiling fit outs.

The upper levels of the street building are inhabited by the general public, and their domesticity is expressed in a similar way, slightly offset from the site boundaries. By doing so, the proposed design subtly references shopfront terrace house proportions, offering an appropriate backdrop to the scale of the street.

Building with Material

Unstabilised Rammed Earth

The site, being located at the current Sydney Metro excavation site for the future Burwood North station, provides an abundance of excavated sub-soil. Currently being transported and dumped to the Western boundaries of the cities, the project proposes to intercept the material and utilize as a primary resource for the construction of new nodes across the proposed sites. Sub soil, free from organic matter, is ideal for unstabilised rammed earth construction with no cement, using clay (ideally 15% of the total make up) as the primary binder and loam, gravel & stones as aggregate. In particular, excavation which occurs closer to harbour (in line with Sydney Metro’s 2032 proposal) would contain on average a 5% sandstone content, obtaining the desired colouring for our proposal.

Rammed earth’s qualities of breathability, fireproofness, thermal mass and biodegradability make it an extremely sustainable construction material. In external walls, erosion control joints allow natural wear to occur at desired points. These joints can be expressed as a tile, or a seam of lime mortar mixture. The lack of cement is what allows the material to breathe, providing a pleasant indoor climate throughout the year. It also means the material is completely recyclable, being able to be patched up, removed, and altered, indicating a continuous interplay between longevity and impermanence.

Post-Tentioned Stone

Post tensioned stone utilises the materials strength in compression to form beams, in a similar way to post tensioned concrete. Often discarded during excavation, stone is an abundant material that can be elegantly expressed through processing procedures and engineered to achieve large spans and form foundations. Both post tensioned stone and rammed earth are construction methods that enable an expression of place through materiality.

1:1 Object – Rammed Earth Wall Fragment

References & Inspirations

“9 Cities with Medieval Plans Seen from Above.” 2020. ArchDaily. November 30, 2020. https://www.archdaily.com/952084/9-cities-with-medieval-plans-seen-from-above.

“Andrew Burgess Pittwater House | Inhabitat - Green Design, Innovation, Architecture, Green Building.” 2014. Inhabitat - Green Design, Innovation, Architecture, Green Building | Green Design & Innovation for a Better World. October 21, 2014. https://inhabitat.com/australias-pittwater-house-opens-and-closes-with-timber-shade-facade/andrew-burgess-pittwater-house3/.

“Architectural Poetry: House in the Hills.” 2020. ArchitectureAu. 2020. https://architectureau.com/articles/house-in-the-hills/#.

Ankitha Gattupalli. 2024. “Temporary Architecture in India: Marketplaces and Bazaars.” ArchDaily. March 25, 2024. https://www.archdaily.com/1014809/temporary-architecture-in-india-marketplaces-and-bazaars?ad_source=search&ad_medium=projects_tab&ad_source=search&ad_medium=search_result_all. Bacon, Edmund N. 1976. Design of Cities. Penguin Books.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio. 2011. The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture. Cambridge: Mit Press.

Dogma. 2022. Living and Working. MIT Press.

Fernando Chueca Goitia. 2011. Breve Historia Del Urbanismo. Alianza Editorial Sa.

Hall, Peter, and Nicholas Falk. 2014. Good Cities, Better Lives : How Europe Discovered the Lost Art of Urbanism. London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

Healey, Patsy. 2006. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies. Routledge.

Jacobs, Jane. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

Larice, Michael, and Elizabeth Macdonald. 2013. The Urban Design Reader. Routledge.

“‘Living Together Is Only Possible If There Is Always the Possibility to Be Alone.’ – Dogma Studio’s Hard-Line Look at Architectural Solitude.” n.d. Archinect. https://archinect.com/features/article/149959097/living-together-is-only-possible-if-there-is-always-the-possibility-to-be-alone-dogma-studio-s-hard-line-look-at-architectural-solitude.

Memmott, Paul, Richard Hyde, and Tim O’Rourke. 2009. “Biomimetic Theory and Building Technology: Use of Aboriginal and Scientific Knowledge of Spinifex Grass.” Architectural Science Review 52 (2): 117–25. https://doi.org/10.3763/asre.2009.0014.

Mumford, Lewis. 1961. The City in History : Its Origins, Its Transformations, Its Prospects. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

Petridou, Christina. “Bangkok Project Studio Constructs Grand Gable Roof Pavilion for Thailand Festival.” Designboom | Architecture & Design Magazine, October 18, 2023. https://www.designboom.com/architecture/bangkok-project-studio-grand-gable-roof-pavilion-thailand-festival-boonserm-premthada-10-18-2023/.

“Sean Godsell Unveils Melbourne’s Inaugural ‘MPavilion.’” 2014. ArchDaily. October 8, 2014. https://www.archdaily.com/554942/sean-godsell-unveils-melbourne-s-inaugural-mpavilion.